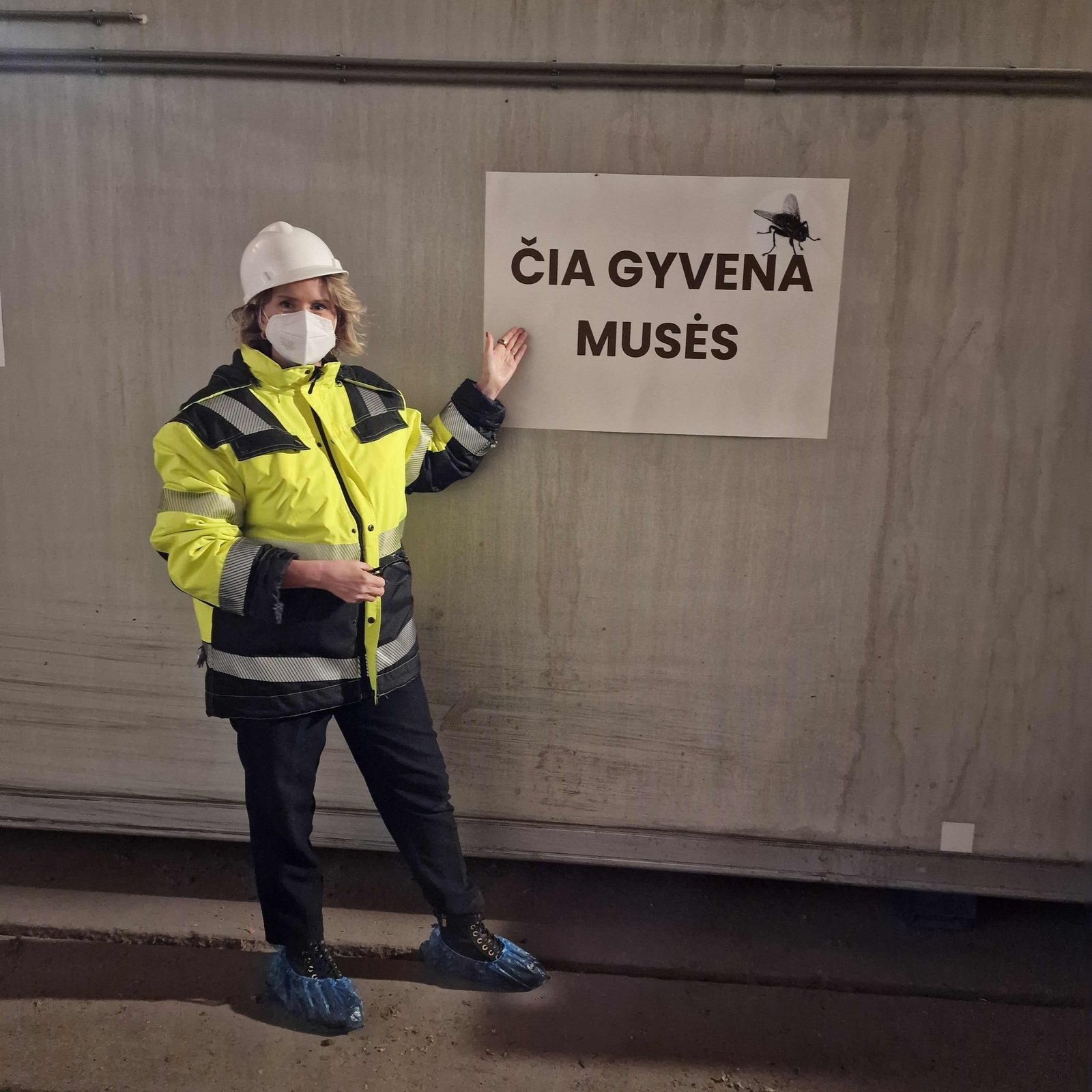

The flies have moved into what’s being playfully called a “wellness retreat” – that’s how Energesman employees describe the new, temporary home of their houseflies. Following the fire at the Vilnius waste sorting facility, fly larvae bred on household kitchen waste have been relocated to the Chemical Ecology and Behaviour Laboratory (CHEEL) at the Nature Research Centre (NRC), part of the State Research Institute, where they will remain under the care of scientists until the facility’s infrastructure is restored. Fortunately, the colony of Musca domestica – specially imported from the Netherlands for organic waste processing – has been preserved.

This pioneering solution for managing kitchen waste in the Vilnius region recently attracted international attention: the BBC published a feature on this Lithuanian innovation, highlighting the use of fly larvae to process kitchen waste. You can read the full article here.

Favourable conditions for survival and research

“Shortly after the incident, we moved the flies and their larvae to the NRC CHEEL lab, where they have adapted well. Scientists are now ensuring they have suitable conditions to survive and thrive until we’re able to bring them back to the facility. This period also provides valuable opportunities for observation and research,” says Algirdas Blazgys, CEO of Energesman.

In the lab, scientists are carefully managing reproduction to avoid overpopulation. Cooler temperatures are used to slow the development of the pupae, or puparia, ensuring population stability rather than rapid growth.

“Most puparia – also called cocoons or ‘beans’ – are stored at lower-than-normal temperatures to slow down their development and preserve the existing population. The same applies to adult flies and larvae – we maintain a cooler environment to support a stable colony,” explains Gabriele Bumbulyte-Zukeviciene, PhD candidate at the NRC and a researcher working with the colony.

Currently, puparia are kept at 6°C, while adult flies and larvae are maintained at 18°C. Once the larvae reach the puparia stage, they are moved to cooler conditions to further slow development.

Tailored habitats for every species

At CHEEL, each species is kept in a separate space to ensure that their unique environmental needs are met. According to Bumbulyte-Zukeviciene, the houseflies and larvae from the waste sorting facility have a dedicated environment where temperature, humidity, and food supply are carefully controlled.

Flies are housed in special enclosures equipped with food and water sources, egg-laying substrates, and temperature controls that support their natural life cycle. Eggs are routinely collected and moved through the growth stages. Once larvae reach the puparia stage, they are either returned to the breeding cycle or stored to maintain population continuity.

“Until now, we’ve been feeding the flies and larvae with standardised, balanced feed to ease the transition to the lab environment, but we’re now preparing to introduce food waste and test additives that improve nutritional value,” adds Bumbulyte-Zukeviciene.

Market-ready innovation

Earlier this year, Energesman publicly introduced one of Europe’s most innovative solutions for processing household kitchen waste: breeding fly larvae on food scraps collected in orange bags from Vilnius county residents.

After being shredded and mixed with water, the contents of the orange bags were processed into an organic feedstock for the larvae. Once grown and dried, the larvae were intended for use in the production of biofuels and protein-based industrial materials – including paints, furniture, adhesives, and lighting – while the leftover biomass served as fertiliser or fishing bait.

Energesman invested EUR 1 million into bespoke larval rearing equipment designed in the Netherlands specifically for Vilnius needs. An additional EUR 1.1 million was invested by the regional waste management centre, VAATC, into automated systems for unpacking the orange bags and cleaning the food waste, preparing it for larval processing.

Return to facility in sight

“The equipment for processing food waste was not damaged – only covered in soot. We’re currently repairing one of the fixed sorting lines and working towards fully restoring factory operations, including larval rearing,” says Blazgys.

The full facility is expected to be operational again later this year. Scientists note that the fly colony is ready to return at any time – their stay at the lab is only temporary. It also offers researchers an opportunity to study the species and ensure its continuity.

“The most important thing is that the flies survived and have retained their potential,” says Bumbulyte-Zukeviciene.

At the Vilnius Mechanical-Biological Treatment (MBT) facility operated by Energesman, mixed and organic waste from across the region is again being processed – currently with mobile equipment, while preparations are made to rebuild the plant.